Abstract

In Turkey, Agricultural Development Cooperatives are very important for bringing the resources in rural area to the economy, establishment of agro-industrial facilities for processing agricultural products and preventing migration from rural area to cities. While the number of Agricultural Development Cooperatives in Turkey was 6000 in 1974, it rose to 7196 in 2017. Total number of partners of these cooperatives is 775255.

The aim of the study is to reveal financial structures of Agricultural Development Cooperatives within the scope of the research by using ratio analyses. Data in this study were retrieved from income statement and balance sheets belonging to 2016 of 70 Agricultural Development Cooperatives in the Western Mediterranean Region. Ratio analyses were classified as financial structure ratios, activity efficiency ratios and profitability ratios in this study. Financial analysis was conducted for Agricultural Development Cooperatives by comparing the values obtained as a result of analysis with the standard values. Findings obtained from this study and other similar studies suggest that one of the most significant problems of agricultural development cooperatives is finance. As a result of the study, it was determined that the cooperatives studied were not in financial sufficient level. The financial weaknesses of the cooperatives examined mean that they can face financial problems in the long run. Financial insufficiency poses a risk in terms of the continuity of the surveyed cooperatives.

DOI: 10.30682/nm1902h

Asaf Ozalp*

* Department of Agricultural Economics, Faculty of Agriculture, Akdeniz University, Antalya, Turkey.

Corresponding author: asafozalp@hotmail.com

Cite this Item: Ozalp A., 2019. Financial Analysis of Agricultural Development Cooperatives: A Case of Western Mediterranean Region, Turkey, New Medit, 18 (2): pp. 119-132, http://dx.doi.org/10.30682/nm1902h

1. Introduction

As of the second half of the 19th century, cooperatives became important instruments in facilitating social and economic development in all countries and they currently maintain these functions. The cooperative system is accepted as a significant social movement in the world, as it contributes to the protection of environment and creation of employment and it serves as an essential mean in the social and economic development of countries (Mulayim, 1999). Being one of the means of self-help, the cooperative system has been implemented in developing countries according to the models in the European countries. The UK, Germany and France spread their own principles of cooperative system to the whole world, which were accepted and put into use by the developing countries (Kivanc, 1982).

Agricultural cooperatives are socioeconomic organizations established to protect the economic rights of farmers and thus to obtain a higher level of profits (Laidlaw, 1981). Cooperatives are the most frequently encountered institutions in the world following the governmental institutions for the fields of agricultural production and processing, and marketing of products (Erkus and Ozudogru, 2005). In the modern world, it is accepted by everyone that commercial enterprises have such a central importance in directing the social life. The development of the capital markets, the requirement of monetary-credit institutions to be based upon firmer grounds, while extending funds and the tendency of enterprises to grow, have currently put the financial analysis in an exceptionally important position (Acar, 2003).

There is a lot of scientific research done about cooperatives. Martin and Guerra (2011), aim to show the strategies of the cooperative sector for the development of new channels of international commercialization that allow to mitigate the effects of the risk. Coren and Clamp (2014), asks what we can learn from the use of a shared-services co-operative to meet the needs of small scale winemakers in a regulated market in their research. Campos-Climent and Sanchis-Palacio (2015), checks for the existence of a significant relationship between organizational size and performance in agri-food firms, namely in Spanish fruit and vegetable (F&V) cooperatives. The study founds show the absence of a significant positive relationship between size and performance in agri-food firms. Othman et al. (2014) expect to uncover competitive advantage as an indicator of business success among cooperative organizations in their study. Xiangyu Guo (2010), aim to identify the environment pressures that farmers faced in food safety, and explain why the agriculture cooperatives can be an effective organization in SCM. Galati et al. (2015), contributes to assessing the effectiveness of the GH measure to contribute in reducing the supply of wine grapes, and thus contrasting the fall of wine prices in those years when especially abundant productions are expected. Fanzini and Russo (2014), compare the profitability of cooperatives and investor-owned firms in the Italian wine sector. Gomez (2006), aim to measure productivity and efficiency of horticultural co-operatives. Hammad Ahmad Khan et al. (2016), purpose in their paper to investigate the factors affecting co-operatives performance by focusing on the roles of its intangible assets which are in the form of intellectual capital and members’ participation. Valentinov (2007), develops an organizational economics explanation for agricultural cooperatives by building upon the transaction cost theory of family farms.

Financial analysis is an activity that includes the association between various accounts in financial statements as well as their measurement and interpretation. The aim of the financial analysis is to present the liquidity position, profitability, capital structure and assets utilization position of an enterprise. By conducting a financial analysis, the current position of the enterprise is evaluated allowing one to take decisions for the future. Financial analysis may be conducted by the enterprise as well as institutions or investors granting loans to the enterprise (Yener, 2006). Some of the studies conducted on financial analysis of agricultural cooperatives are Lerman and Parliament (1991), Binion (1998), Ozudogru (2004), Akono et al. (2005), Carlberg et al. (2006), Surmeli (2006), Arslan (2007), Banaszak (2007), Boyd et al. (2007), Gurung and Unterschultz (2007), Laziková et al. (2008), McKee (2007), McKee (2008), Cosgun and Bekiroglu (2009), Pashkova et al. (2009) and Akcaoz et al. (2011).

Agricultural development cooperatives are established to attain several goals, such as making the agricultural enterprises more efficient, regulating marketing activities, meeting the need for inputs, loan, etc., and ensuring the establishment of rural industry.

Development of agricultural cooperatives in Turkey are satisfactory in terms of the number of cooperatives, but these cooperatives are not economically active. One of the main reasons for this is the weak financial situation of agricultural development cooperatives. The fact that the financial status of the Agricultural Development Cooperatives is revealed implies a clearer determination of the problem. This situation necessitated such a study.

The objective of this study is to examine the accounting records of the Agricultural Development Cooperatives in the Western Mediterranean Region of Turkey and to conduct their financial analyses.

1.1. Current position of the Agricultural Development Cooperatives in Turkey

The first application of modern cooperatives in Turkey, established by the state in 1863, «the country chests» with (like structure of agricultural credit cooperatives) are considered to begin. However, the first essential development in cooperatives is found in the Republican Period. Today is located 84232 cooperatives in 26 different species in Turkey, while the total number of these partners are 8109225. Of the approximately 84000 cooperatives in the country, 12000 are for agricultural purposes and 72000 for non-agricultural purposes.

The cooperatives in Turkey are established and carry out their activities in accordance with three separate laws according to their types:

1. The Cooperatives Law no. 1163: It is the primary law which governs the cooperatives sector. This Law which helps many cooperatives to be established and developed came into force on 24.4.1969. In accordance with Article 98 of the Cooperatives Law, in cases where there are no explanations on the contrary, the provisions concerning Joint Stock Companies in the Turkish Trade Law are applied.

2. The Law no. 1581 on Agricultural Credit Cooperatives and Unions: Including specific provisions on the establishment and functions of agricultural credit cooperatives, this Law came into force on 18.4.1972. In cases where there are no explanations, the provisions of the Cooperatives Law no. 1163 are applied.

3. The Law No. 4572 on Agricultural Sales Cooperatives and Unions: This is the law which was issued particularly for the agricultural sales cooperatives. This law came into force on 1.6.2000 and governs the issues specific to agricultural sales cooperatives and unions. In cases where there are no explanations, the provisions of the Cooperatives Law No. 1163 are applied (Anonymous, 2012).

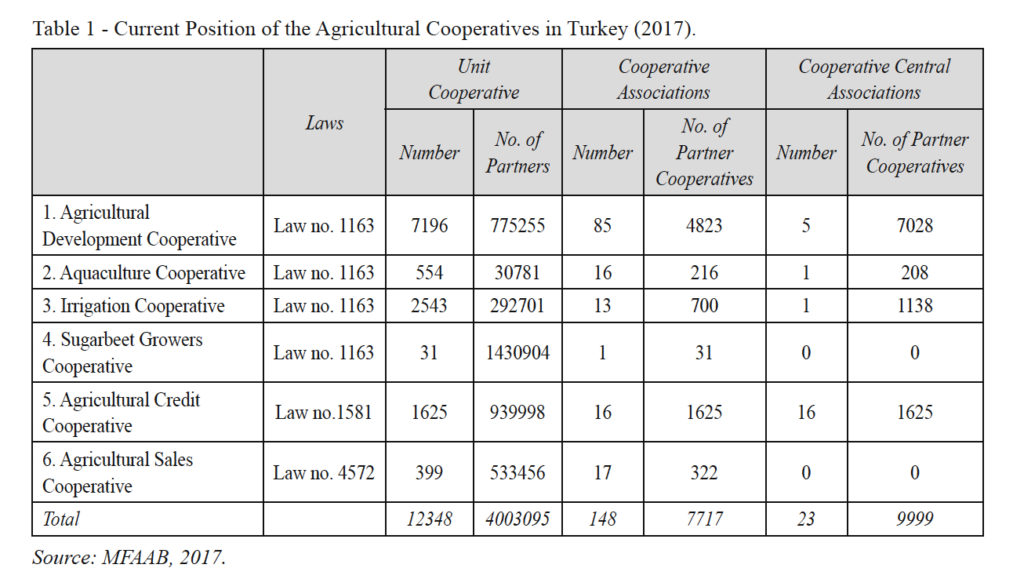

The cooperative system has been used in our Turkey as a means for the balanced development of the society just like the other developed and developing countries. The number of agricultural cooperatives in 2017 was 12348 and the number of partners was approximately 4 million (Table 1).

In Table 1, it is demonstrated that there are 7196 agricultural development cooperatives that are subject to the Law no. 1163 and the number of partners in these cooperatives is 775255. Some of the Peasant Cooperatives, Livestock Cooperatives, Forestry Cooperatives, and Tea Cooperatives gathered and established regional associations and some of these associations were included in a horizontal organization with centralization. The ratio of agricultural development cooperatives to total cooperatives is 8.54% and the rate of agricultural development cooperatives in agricultural cooperatives is 58%. According to the number of partners, the number of agricultural development cooperatives is 9.35% of the total number of cooperative partners, the share of agricultural cooperatives among agricultural cooperatives is 19%.

According to the Cooperatives Law no. 1163, it is the duty of the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Animal Breeding to establish, organize, and supervise the agricultural cooperatives. The Law no. 3476 which amended the article 25 in the Cooperatives Law no. 1163 was issued in 1998. The articles forming nine types of associative structures for cooperatives, which were formerly in effect, were assembled under four types of articles. To mention, these are Agricultural Development, Irrigation, Aquaculture, and Sugar beet Growers. In Turkey, Agricultural Development Cooperatives are very important for transferring rural resources to the economy, establishment of agro-industrial facilities for agricultural processing, and preventing migration from rural to urban areas (Inan et al., 2000). Aims of Agricultural Development Cooperatives are as following:

1. Supporting agricultural production improvement of their partners,

2. Fostering macro and micro projects by engaging in procurement, supply, operating, marketing, and assessment activities,

3. Assisting their partners in utilization of their economic power and new investment decisions,

4. Facilitating circles of trade (Anonymous 2004),

5. Stilizing natural resources to increase the economic power of their partners.

6. Taking actions for development of handicrafts, domestic crafts, and agro-industry.

The policy of the state on the cooperatives has been included in the Turkish Constitution since 1961. Moreover, the advancement of cooperatives has often been taken into consideration in the Development Plans and the agricultural cooperatives in particular have been considered as one of the most important development policies. The state used its regulatory power, enacted general and special cooperatives laws and chose to give a different legal status to the cooperatives from the other organizations. Moreover, the state has leaded the way to establish and develop several cooperatives.

Today, some cooperatives types are given financial support by the state and these financial aids are aimed for the agricultural sector. Within this framework, project support is provided to the agricultural cooperatives in accordance with the provisions of the Regulation on the Credits to be utilized by the Agricultural Cooperatives. Agricultural sales cooperatives have recently utilized from Support and Price Stabilization Fund (Anonymous, 2012).

1.2. The performance of Turkey in terms of the practices in the world

When the systems and practices in the other countries are compared, it is a fact that the cooperatives in Turkey have achieved the wished performance in terms of their potentials. Within this regard, the deficiencies, troubles and incapability faced by the cooperatives in Turkey in comparison with the successful cooperatives in the world are listed under the following titles (Anonymous, 2012):

- Due to the insufficient superior organization, the services on training, financing, audit, consultancy, technical and legal support for the cooperatives are low.

- The share of the cooperatives in the figures related with “National Income, Production, Employment, Investment, Foreign Trade” and their share in the sector which they provide services in are not known well in Turkey.

- The cooperatives in Turkey can only develop in terms of their numbers (the number of the cooperatives) and a sound cooperative structure and understanding have not been ensured.

- The rate of establishing cooperatives in the community is low.

- The cooperatives are more common in housing and agricultural sector, but no cooperative has been established in the sectors such as retailing, credit- financing, insurance, the energy generation, education and health.

1.3. Cooperatives problems in Turkey

Cooperative movement has a very important position in terms of the development, efficiency and productivity of the Turkey’s agricultural sector. It is not possible to say that the cooperative movement, which has great importance especially in terms of employment, is still in the desired level. Because the cooperative movement has come to this day with many problems still not solved since the day it was established. Despite the fact that the cooperative problems have been mentioned in previous studies, in the 5-year development plans and finally in the Strategy and Action Plan of Agricultural Organizations Cooperatives (Anonymous, 2012), the necessary solutions could not be implemented and the problems continued. The main problems with cooperatives in Turkey are classified in different ways by different researchers. However, there is a consensus for fundamental problems (Mulayim, 1990; Anonymous, 1997; Mulayim, 2013; Rehber, 2011; Yilmaz et al., 2008; Anonymous, 2012; Ozalp and Yilmaz, 2014). These problems can be classified as: (a) State and cooperative relations, (b) Legislation problems, (c) Management and Audit problems, (d) The financing and capital problems, (e) Problem of higher organization and cooperation, (f) Education and research problems, (g) Partners-cooperative relationships and trust problems.

(a) State and cooperative relations; States and cooperative relations, despite the positive developments in Turkey, it is still possible to say whether the desired level is reached. Especially in the Agricultural Credit Cooperatives, it can be said that the principle of independence of the cooperatives cannot be provided. On the other hand, uniform contracts facilitate the establishment of cooperatives however, it is not possible for cooperatives, which have reached a certain capacity, to form their own contracts despite the legitimacy of the legislation.

(b) Legislation problems; Cooperative legislation shows a complex and disorganized structure. This leads to confusion and resource waste, and on the other hand it prevents integration between cooperatives.

(c) Management and Audit problems; In order for co-operatives to be able to adapt to changing conditions and be successful, managers need to have the knowledge and skills in managing business functions and management functions. In addition, cooperative principles and values have been adopted by cooperative managers and management activities have to be carried out in this direction. The failure of cooperative managers has often prevented the co-operatives from longevity and has led to the closure of cooperatives.

(d) Financing and capital problems; one of the main problems of Turkey’s agriculture, agricultural enterprises is very small at a great. Moreover, agricultural enterprises do not have sufficient capital. This situation is naturally reflected in cooperatives. The financing and capital problem is one of the most important problems facing the development of cooperatives. This shortfall reduces the investment potential of cooperatives. The main reasons for this situation can be listed as low share of partnerships, lack of knowing how cooperatives will reach appropriate financing, and inadequacy of state supported financial resources. It is possible to solve this problem in two ways. The first is the provision of a cooperative structure with high entry capital (New Generation Cooperative Structure) and another is state-supported long-term credit lines. In the transition to the new generation cooperative structure, the small and low capitalization of agricultural enterprises prevents this solution in the short term and causes the second option to be kept on the front line. In the transition to the new generation cooperative structure, the small and low capitalization of agricultural enterprises prevents this solution in the short term and causes the second option to be kept on the front line. There are two main reasons why cooperatives are not able to benefit from the investment supports that have been implemented in recent years. The first of these is that the capacity of the cooperatives to develop investment projects is insufficient. It is not possible for unit co-operatives to solve this situation alone.

(e) Problem of higher organization and cooperation; the concept of integration is considered to be the gathering of entrepreneurs as a whole from the economic and legal perspective. In other words, it is said that economic units that have complementary functions complement each other and become a body (Cıkın and Karacan, 1994). In order for this integration to be achieved, it is necessary to complete the horizontal and vertical organization of the cooperatives. It should be ensured that the cooperatives actively cooperate with one another through the upper organization. This has not been achieved yet.

(f) Education and research problems; Turkey has serious shortcomings in the cooperative education. Cooperative education is limited to compulsory or elective cooperative lessons in several faculties. However, a cooperative culture is more than just a lesson, to transfer to the next generation of cooperative culture is an essential condition in the development of cooperatives.

(g) Partners-cooperative relationships and trust problems; One of the major problems of cooperatives in Turkey is a problem partners cooperative relations. There is a problem of confidence in cooperatives in Turkey. In a survey conducted, the presence of the ethical values of cooperatives, has been shown to improve performance gained from the cooperative partners. It has been determined that the trust of the partners to the managers has a significant influence on the performance of the partners from the cooperatives loyalty and cooperatives (Bilgin et al., 2005).

Researchers has been done many research on cooperatives in Turkey. A part of the studies on cooperatives in Turkey related to the economic analysis of cooperative partners (Yercan, 1996; Acar and Yildirim, 2000; Dedeoglu and Yildirim, 2006), while some of them examine the socio-economic activities of the cooperative (Yildirim and Acar, 1999; Karli ve Celik, 2003; Ozdemir, 2005; Unal and Yercan, 2006; Serinikli and Inan, 2007; Unal et al., 2009). Also in 2012 by the Ministry of Trade and Customs “Turkey Cooperative Strategy and Action Plan 2012-2016” has been prepared and demonstrated vision and targets in Turkey’s cooperatives.

This study, which reveals the financial structure of co-operatives, is the first work to be done on this issue in the country.

2. Material and method

2.1. Material

The material of the study is composed of the data obtained from the primary and secondary sources. Primary data consist of the accounting records of the agricultural development cooperatives in the region of Western Mediterranean. Secondary data were retrieved from publications of the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Animal Breeding, General Directorate of Organization and Support, Turkish Cooperatives Institution and TURKSTAT and from other studies alike.

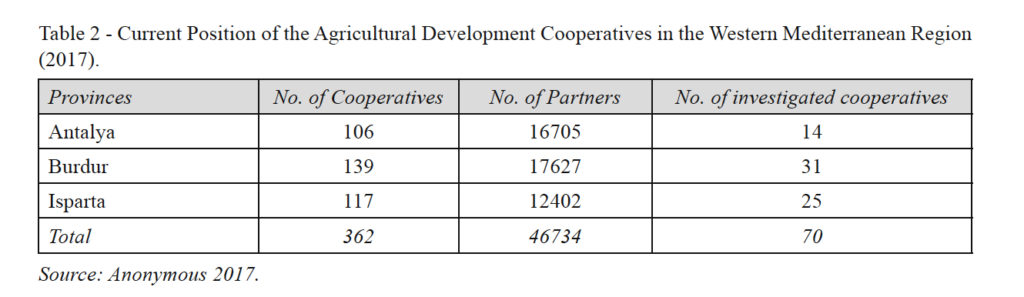

As of 2017, there were 362 agricultural development cooperatives in the Western Mediterranean region, composed by three provinces namely Antalya, Burdur and Isparta. 70 of these cooperatives investigated financially cooperatives in the scope of this research (Table 2). Cooperatives have been selected among the cooperatives which keep their records properly.

The year-end detailed income statement, estimated budget, year-end balance sheets of these 70 active cooperatives of the Western Mediterranean region were used within the study for financial analyses. The required data was obtained from the activity reports of 2016.

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Liquidity ratios

Liquidity ratios help determining the payment opportunities of the liabilities due by demonstrating the monetary position of the enterprise. It is used to determine the capacity of the enterprise to pay its current liabilities by relating its current assets and current liabilities (Arslan, 2007). Liquidity ratios can be listed as follows (Akguc, 1984):

1. Current Ratio;

2. Acid-Test Ratio;

3. Cash Ratio.

Current Ratio (Working Capital Ratio): It indicates the capacity of the enterprise to pay its current short term liabilities or to which extent the realizable assets may cover the current liabilities (which will become due in the current period). Current ratio shows how much dollars of current assets there are, against each dollar of liability. This ratio is preferred to be 2 for developed countries, whereas a ratio of 1.5 is deemed to be enough in developing countries. Current ratio is calculated as follows:

Current Ratio = Current Assets / Current Short Term Liabilities (1)

Liquidity Ratio (Acid test ratio): This ratio is a ratio that accompanies the current ratio and empowers its interpretative function. The ratio can be calculated with division the value computed by extracting the stocks from current assets, by current short term liabilities. Acid test ratio refines the current ratio. The reason is that it excludes the stocks which are generally more difficult to convert into cash than other items of the current assets (Akguc, 1984). Acid test ratio may be regarded as sufficient if it is 1. It suggests that there is a current asset worth of 1 dollar excluding stocks for each dollar of current liability (Akdogan and Tenker, 1998; Akcaoz et al., 2011). Acid test ratio is calculated as follows:

Acid Test Ratio = Current Assets-Stocks / Current Short Term Liabilities (2)

Cash Ratio: Cash Ratio, also known as liquid assets ratio, indicates the capability of cash and cash equivalents to cover the current short term liabilities. It is generally accepted that a cash ratio lower than 20% may cause adversity in the cash position of the enterprise (Akdogan and Tenker, 1998; Akcaoz et al., 2011).

Cash ratio = Cash and Cash Equivalents / Current Short Term Liabilities (3)

2.2.2. Financial Structure Ratios

Ratios used in measuring the enterprise’s asset structure and ability to pay long-term liabilities are included in this group. There are three measures referring to financial structure of the enterprise.

Financial Leverage Ratio: This ratio indicates the percentage of the assets, financed by liabilities. Creditors prefer this ratio to be low. A high ratio suggests that the company is financed speculatively, the security margin is narrow for creditors, and the enterprise is open to face with difficulties in payment of the principal instalment and interests due. Despite its undesirable aspects, enterprise owners prefer this ratio to be high. This ratio is preferred to be higher than 50% in developed countries. Considering from the viewpoint of Turkey, it is accepted if it slightly exceeds 50% due to the reasons such as the insufficient strength of the capital market and scarcity of auto financing opportunities (Akdogan and Tenker, 1998). Financial leverage ratio is calculated as follows:

Financial Leverage Ratio = Total Liabilities / Total Assets (4)

Ratio of Equities to Total Assets: It is a ratio that indicates percentage of the assets financed by the owners and shareholders of the enterprise. It presents the enterprise’s long-term ability to pay. A high ratio suggests that the enterprise will not face any difficulty in the payment of its long-term liabilities and their interests. Under normal conditions, this ratio is preferred to be higher than 50% (Akdogan and Tenker, 1998; Akcaoz et al., 2011).

Ratio of Current Liabilities to Total Assets: Ratio of current liabilities to total assets indicates how much of the total liabilities are required to be paid in the short-term. A low ratio is desirable as it suggests a lower level of risk of the enterprise to have difficulty in the payment of debts (Acar, 2003). It is accepted as a general criterion by the Western financial institutions that the ratio of current liabilities to total liabilities (or assets) should be lower than 30%, whereas this ratio is around 50% in the countries that have difficulty in reaching long-term funds and have high levels of inflation (Anonymous, 2008).

2.2.3. Activity Efficiency Ratios

Total Assets Turnover Rate: Total assets turnover rate calculated by dividing the sales revenue by total assets indicates efficiency level of revenue generation of the assets owned by the enterprise. A high rate is desirable (Anonymous, 2008). Total assets turnover rate is calculated as follows:

Total Assets Turnover Rate = Net Sales / Total Assets (5)

Stock Turnover Rate: Another ratio that measures the efficiency of the assets in their use is the stock turnover rate which indicates how many times the stocks were turned over in an accounting year (Anonymous, 2008).

Stock Turnover Rate = Cost of Goods Sold / Average Stock (6)

Accounts Receivable Turnover Rate: Accounts receivable turnover rate is one of the supplementary ratios used in measuring the liquidity position of an enterprise and indicates percentage of the total sales based on credit. The increase of the accounts receivable turnover rate is in favour of the enterprise and indicates that the working capital depends relatively less on the accounts receivable. On the other hand, the declination of the rate indicates that the majority of the working capital is allocated to the accounts receivable (Akdogan and Tenker, 1998; Akcaoz et al., 2011). Accounts receivable turnover rate is calculated as follows:

Accounts Receivable Turnover Rate = Net Sales / Average Accounts Receivable (7)

2.2.4. Profitability Ratios

Ratios used in measuring the degree of efficiency of the enterprise’s equities and liabilities are included in this group (Akdogan and Tenker, 1998; Akcaoz et al., 2011).

Profit / Gross Income (Profit Margin): This ratio indicates the percentage of the profit obtained by the enterprise from its net sales. A high ratio and an increasing trend in this ratio is a favourable indicator for the enterprise (Anonymous, 2008). It may be determined whether this ratio, which provides information on the gross profitability of the enterprise, is sufficient or not by making comparisons with other similar enterprises. A high ratio or an increasing trend is construed in favour of the enterprise (Akdogan and Tenker, 1998; Akcaoz et al., 2011).

Profit / Equity: This ratio, which is calculated with dividing the profit by the equity, indicates the net yield obtained per each unit of equity, and is also called as “equity rate of return” or “financial profitability” (Anonymous, 2008).

Ratio of Operating Profit to Net Sales: This ratio provides information on the business volume profitability of the enterprise and is used in determining to which extent the enterprise is profitable from its main operating activity. A high ratio is favourable for the enterprise (Akdogan and Tenker, 1998; Akcaoz et al., 2011).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. General structure of the Agricultural Development Cooperatives examined

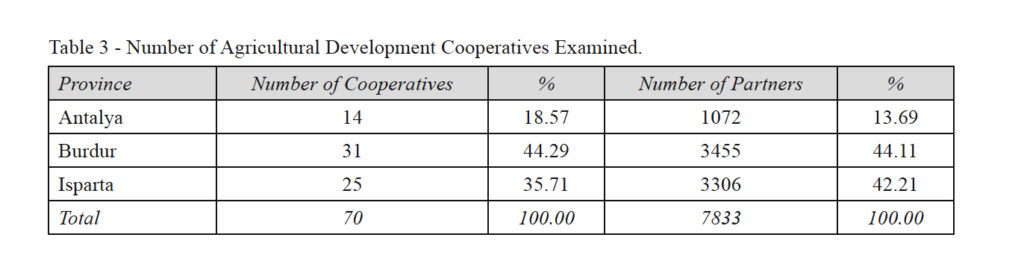

Agricultural development cooperatives within the scope of the study are grouped as to their provinces: Antalya, Burdur and Isparta. 18.57% of 48 cooperatives examined in the study are in Antalya, 44.29% in Burdur, and 35.71% in Isparta province (Table 3).

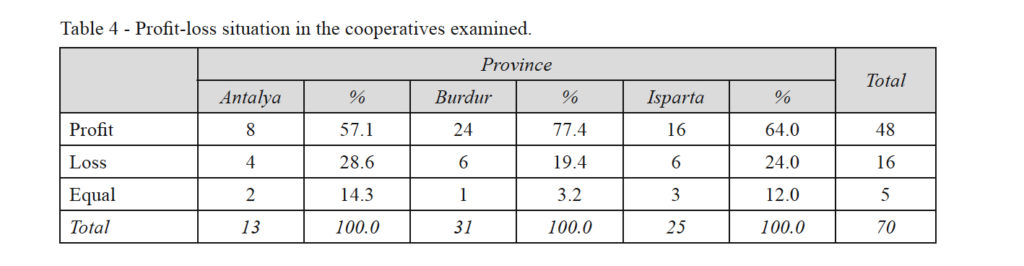

3.2. Profit-loss situation in the cooperatives examined

Agricultural development cooperatives in Turkey are basically non-profit formation. However, it is important for the cooperatives to make profit in terms of the continuity of the cooperatives, meeting the demands of the partners and making necessary investments. When the profit and loss situations of the cooperatives subject to the research are examined, it shows that the profitability status of the cooperatives is not very good (Table 4). Accordingly, a total of 48 cooperatives, 8 in Antalya, 24 in Burdur and 16 in Isparta, achieved operating profit by the end of 2016. 16 cooperatives, 4 in Antalya, 6 in Burdur and 6 in Isparta, declared their operational loss as of the end of the same year, the remaining cooperatives declared neither profit nor loss. It is unlikely that the losing cooperatives will be able to sustain their continuity in the long run.

3.3. Financial analysis of the Agricultural Development Cooperatives examined

Ratio Analysis Method was applied in the determination of Liquidity Ratios, Financial Structure Ratios, Activity Efficiency Ratios and Profitability Ratios of the agricultural development cooperatives within the scope of the study.

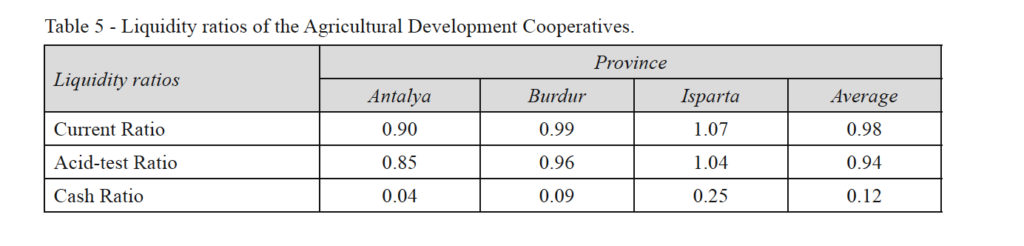

3.3.1. Liquidity ratios

Liquidity ratios are the ratios that measure the enterprise’s liquidity position, that is, its ability to pay its current short term liabilities. Current ratios of cooperatives examined that take place in Antalya and Burdur were found low and signed possession of risks. When the acid-test ratios of the selected agricultural development cooperatives were examined according to their number of partners, it was seen that the cooperatives were in risky positions regarding payment of their current liabilities. Cooperatives should keep their acid-test ratio at 1 or higher. Only the cooperatives in Isparta Province acid-test level were found high than 1. Cash ratios of the cooperatives were found to be above 0.12, which is financially acceptable (Table 5).

Cooperatives in the province of Isparta have been identified as the cooperatives with the highest current ratio. This shows that the cooperatives operating in the province of Isparta do not benefit from short term foreign sources. The highest acid test rate was calculated again in the cooperatives operating in the province of Isparta. In other cases, this ratio is not greater than the desired level of 1 or 1. The cash ratio is above the desired level of 0.20 in development cooperatives operating in the province of Isparta only. In cooperatives operating on the other two, this rate is quite low. This suggests that cooperatives operating in these provinces may be very difficult to pay short term debts.

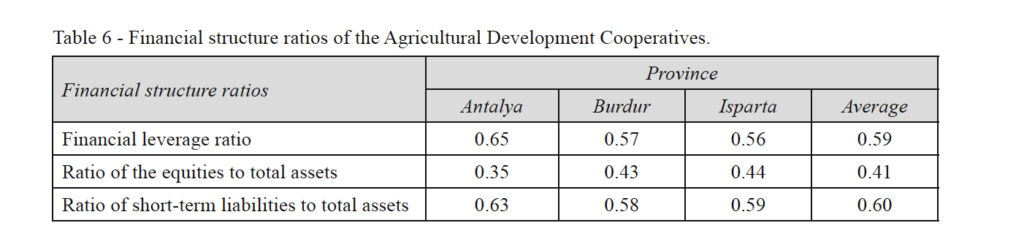

3.3.2. Financial structure ratios

Among the financial structure ratios, financial leverage ratio, ratio of the equities to total assets, and ratio of the short-term liabilities to total liabilities have been studied. It is required that enterprises have a financial leverage ratio of at least 0.50. This ratio is average 0.59 in the agricultural development cooperatives examined, which is quite high (Table 6). A high financial leverage ratio indicates that the assets of the enterprise are financed by equities.

The ratio of the short-term liabilities to the total assets indicates what percent of the assets of the enterprise is financed by short-term liabilities. In other words, it indicates to which extent the total assets are covered by short-term debts. No doubt, the increase of this ratio increases the financial risk as well (Akdogan and Tenker, 1998; Akcaoz et al., 2011). It poses a risk if the ratio of short-term liabilities to assets is high. If this ratio is low, it may be inferred that short-term liabilities are not used as a source of finance. Credit costs should be taken into account while using short-term liabilities. Among the cooperatives examined, the average ratio of the short-term liabilities to total liabilities was found out as 0.60 (Table 6).

For the agricultural development cooperatives covered under the research, the financial leverage ratio was found to be higher than the desired level of 0.5 for each of the three provinces. In the cooperatives operating in the province of Isparta, the ratio of short-term liabilities to total assets is highest at 0.44. The ratio of short-term foreign resources to total resources is highest in Antalya. However, the low rates achieved in all three provinces indicate that operating assets are financed by long-term foreign resources and equity.

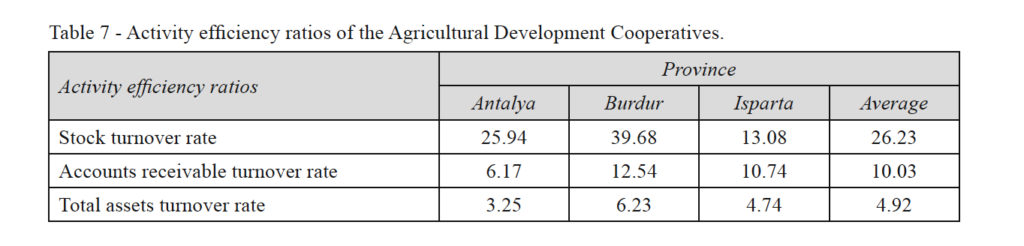

3.3.3. Activity efficiency ratios

This group of ratios measures how efficient the assets of the enterprise are used. The general tendency is a high stock turnover rate, which indicates that the goods of the enterprise are immediately sold without waiting for a long time and the circulation of the goods is at a favourable level. Stock turnover rates of the agricultural development cooperatives examined in the study according to the number of their partners are provided in Table 7. It was seen that the stock turnover rates of the cooperatives are high.

A high stock turnover rate is favorable for enterprises, the average of this ratio is 26.23 among cooperatives. A high stock turnover rate is an indicator of success for enterprises. Accounts receivable turnover rate was found as 10.03 on average in the development cooperatives, while the mean value of total assets turnover rate was 4.92.

A high stock turnover rate is a sign of success. Stock turnover rates of cooperatives categorized by province are higher than all three provinces. The highest stock turnover rate and accounts receivable turnover rate were calculated in the cooperatives operating in Burdur. The total asset turnover rate is again the highest in cooperatives operating in Burdur.

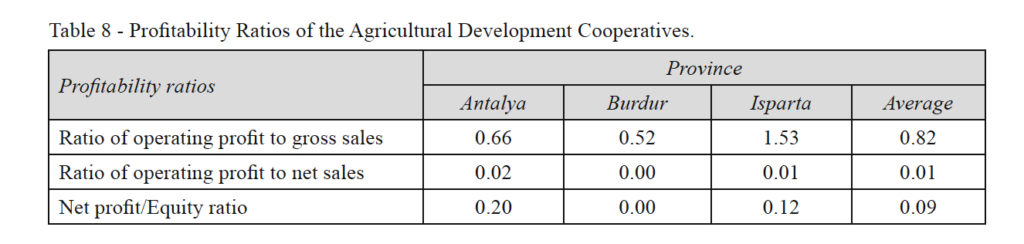

3.3.4. Profitability ratios

It is the main goal of an enterprise to obtain operating profits from sales. A high operating profit with reference to sales indicates that the operating expenses are low and the enterprise is successfully managed. The profitability ratios in the development cooperatives within the scope of this study have been found quite low. In the development cooperatives studied, the average ratio of the operating profit to gross sales was 0.82, the average ratio of the operating profit to net sales was 0.01 and the average ratio of the net profit to equity was 0.09 (Table 8).

The ratio of operational profit to gross sales is highest in cooperatives operating in the province of Isparta. The ratio of operating profit to net sales is calculated at a very low level in development cooperatives operating on all three provinces. The net profit/equity ratio is highest in cooperatives operating in Antalya and lowest in cooperatives operating in Burdur. The data obtained show that cooperatives operating on all three sides are experiencing serious difficulties in terms of profitability.

4. Conclusions

In Turkey cooperatives has a financial problems such as equity. Credit and lack of capital. The financial problems faced by the cooperatives cannot grow and grow to the desired extent. In order for the cooperative movement to fulfill economic and social duties. The solution of financial problems of cooperatives is a priority issue. The aim of this study was to examine the accounting records of the Agricultural Development Cooperatives in three provinces of Western Mediterranean Region pf Turkey and to conduct their financial analyses.

In the Western Mediterranean Region there are totally 362 agricultural development cooperatives and 70 of these cooperatives that examined in this study. In the study the year-end detailed income statements estimated budgets and year-end balance sheets which are required for the financial analysis of the agricultural development cooperatives of the province of Antalya. Burdur and Isparta were obtained from the activity reports of 2016. Ratio Analysis Method was applied in determination of Liquidity Ratios. Financial Structure Ratios. Activity Efficiency Ratios and Profitability Ratios of the agricultural development cooperatives within the scope of the study. Current average ratios in the cooperatives examined were slightly lower than normal (Current Ratio: 0.98; Acid-test Ratio: 0.94; Cash Ratio: 0.12). Current ratio and Acid-test ratio should be 1 or more, cash ratio should not be less than 0.20. When the acid-test ratios of the agricultural development cooperatives in the study were examined according to their number of partners it was seen that the cooperatives were in a risky position regarding the payment of current liabilities as of 2016. Cooperatives should keep their acid-test ratio at the level at 1 minimum. In the study the financial leverage ratios of the agricultural development cooperatives were found as 0.94 which is quite high. A high financial leverage ratio indicates that the assets of the enterprise are financed by equities.

The main objective of cooperative partners in agricultural activities is to achieve profits. Cooperatives are acting in line with these expectations in their activities. However the results show that cooperatives are very difficult to make profits and profit by maintaining very low profits. This situation represents can encounter difficulties in terms of co-operatives in the long term to sustain their activities.

Findings obtained from this study and other similar studies suggest that one of the most significant problems of agricultural development cooperatives is finance. Cooperatives are unable to produce effective and efficient services due to financing and skilled personnel problems. Cooperatives having limited economic power are unable to properly fulfil physical services related to marketing such as processing, storage and transportation. The efforts of middlemen, brokers and commission merchants regarding cooperatives as their rival to preclude the capital accumulation. Thus solidarity and development bring along financial problems and impede the improvement of development cooperatives.

References

- Acar I., Yildirim I., 2000. Economic analysis of joint enterprises in Dönerdere Agricultural Development Cooperative operating in the dairy industry. Yüzüncü Yıl University. Faculty of Agriculture. Journal of Agricultural Sciences (J. Agric. Sci.), 10(1): 61-70.

- Acar M., 2003. Financial Performance Analysis in the Farm. Erciyes University Journal of Economics and Administrative Sciences, 20(1-6): 21-37.

- Akcaoz H., Demir T.N., Kizilay H., Ozalp A., 2011. Financial Analysis of Agricultural Development Cooperatives: A Case of Antalya. Turkey. II. AGRIMBA-AVA Congress Dynamics of International Cooperation in Rural Development and Agribusiness. Wageningen, Nederland.

- Akdogan N., Tenker N., 1998. Financial Tables and Financial Analyses Techniques. Gazi Publishing, 6th ed. Ankara.

- Akguc O., 1984. Examined Credit Demands, Ankara: Turkey Isbank Cultural Publications, 160-161.

- Akono J.H., Nganje W.E., Kaitibie S., Gustafson C.R., 2005. Investors’ Expectations of New Generation Cooperatives Equity. Agribusiness and Applied Economics Report No. 575. North Dakota State University.

- Anonymous, 1997. Cooperatives in Turkey. Turkish Cooperatives Authority Publication No. 88. Ankara.

- Anonymous, 2004. Turkish Republic Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs II. Agriculture Council. Ankara: 10th Commission Agricultural Organizations, 28 pp.

- Anonymous, 2008. Turkish Republic Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Ankara: Financial Management for Farmer Organizations: 93-116.

- Anonymous, 2012. Cooperative Development Strategy and Action Plan of Turkey 2012-2016.

- Anonymous, 2017. Turkish Republic Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Antalya.

- Arslan Y., 2007. Financial Analysis of Afyon Sugarbeet Growers Cooperative. MSc Thesis. Eskisehir Anadolu University. Eskisehir, 135 pp.

- Banaszak I., 2007. Testing Theories of Cooperative Arrangements in Agricultural Markets. Results from Producer Groups in Poland. IAAE-104th EAAE Seminar. 6-8 September 2007. Corvinus University of Budapest.

- Bilgin N., Ergun E., Aydınlı H., 2005. The Effects of Ethical and Trustful Partners on the Performance of Agricultural Cooperatives. Third sector cooperatives, 148: 66-86.

- Binion R.W., 1998. Understanding Cooperative Bookkeeping and Financial Statements. USDA Cooperative Information Report, 57.

- Boyd S., Boland M., Dhuyvetter K., Barton D., 2007. Determinants of Return on Equity in US. Local Farm Supply and Grain Marketing Cooperatives. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 39(1): 201-210.

- Campos-Climet V., Sanchis-Palacio J.R., 2015. How much does size matter in agri-food firms?. Journal of Business Research, 68: 1589-1591.

- Carlberg J.G., Word C.E., Holcomb R.B., 2006. Success Factors of New Generation Cooperatives. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 9(1).

- Cıkın A., Yercan M., 1995. Producer Organization in Agriculture. Turkey Agr. Eng. IV. Technical Congress Reports. Ankara, 47-71.

- Coren C., Clamp C., 2014. The Experience of Wisconsin’s Wine Distribution Co-operatives. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, 2: 6-13.

- Cosgun U., Bekiroglu S., 2009. Financial Analysis of Forest Village Agricultural Development Cooperatives for Using Productive of ORKOY Cooperative Investments (Antalya Agricultural Development Cooperatives Example). 2nd Forestry Socio- Economics Problems Congress. 19-21 February 2009. Isparta.

- Dedeoglu M., Yildirim I., 2006. Economic analysis of joint enterprises in Emek Agricultural Development Cooperative. Yuzuncu Yil University Agricultural Faculty. Journal of Agricultural Sciences (J. Agric. Sci.), 16(1): 39-48.

- Erkus A., Ozudogru H., 2005. Economic Analysis of Kirklareli Koy-Coop. Union and Examined of Influences to Cooperative Success of Managers. Journal of Turkish Cooperation Institution, 150(10-12): 3-22.

- Fazzini M., Russo A., 2014. Profitability in the Italian wine sector: An empirical analysis of Cooperatives and Investor-owened firms. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 4(3): 128-135.

- Galati A., Borsellino V., Crescimanno M., Pisano G., Schimmenti E., 2015. Implementation of green harvesting in the Sicilian wine industry: Effects on the cooperative system. Wine Economics and Policy, 4: 45-52.

- Galdeano Gómez E., 2006. Productivity and efficiency analysis of horticultural co-operatives. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research, 4(3): 191-201.

- Gurung R.K., Unterschultz J.R., 2007. Evaluation of Factors Affecting the Choice of Pricing and Payment Practices by Traditional Marketing and New Generation Cooperatives. Journal of Cooperatives, 20: 18-32.

- Hammad Ahmad Khan H., Yaacob M.A., Abdullah H., Abu Bakar Ah S.H., 2016. Factors affecting performance of co-operatives in Malaysia. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 65(5): 641-671.

- Inan I.H., Gülçubuk B., Ertuğrul C., Kanturer E., Baran A., Dilmen O., 2000. Organized of Rural Area in Agriculture in Turkey. Turkey Agriculture Engineering V. Technical Congress, 38: 145-175.

- Karli B., Celik Y., 2003. The Effectiveness of the Agricultural Cooperatives and Other Farmer Organizations in the GAP Region on Regional Development. TEAE Publication No. 97. Ankara.

- Kivanc C., 1982. Agricultural Cooperation in Turkish Economy. Ankara: Turkey Cooperation Institution Publications, 48.

- Laidlaw A.F., 1981. Cooperatives in 2000 (Translated by Haluk Uzel). Ankara: Yol-Coop Publications, 7.

- Laziková J., Bandlerova A., Schwarcz P., 2008. Agricultural Cooperatives and their Development after the Transformation. Tradition and Innovation – International Scientific Conference of Agricultural Economists. Szent Istvan University. 3-4 December 2007.

- Lerman Z., Parliement C., 1991. Size and Industry Effects in the Performance of Agricultural Cooperatives. Agricultural Economics, 6(1): 15-29.

- Martín Lopez V.M., Ruiz Guerra I., 2011. Strategic Management for the Internationalization and Cooperative Markets. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24: 769-780.

- Mckee G., 2007. The Financial Performance of North Dakota Agricultural Cooperatives. Department of Agricultural Economics North Dakota State University. Agribusiness and Applied Economics Report No. 624.

- Mckee G., 2008. The Financial Performance of North Dakota Grain Marketing and Farm Supply Cooperatives. Journal of Cooperatives, 21: 15-34.

- MFAAB., 2017. Ministry of Food. Agriculture and Animal Breeding of Turkey. Available at: https://www.tarim.gov.tr/.

- Mulayim Z.G., 1990. Basic Problems of Turkish Cooperatives and Suggestions for Solution. Istanbul: Friedrich Ebert Foundation.

- Mulayim Z.G., 1999. Cooperation. 3rd ed. Ankara: Yetkin Publishing.

- Mulayim Z.G., 2013. Cooperatives. 7th Print. Ankara: Yetkin Publications.

- Othman R., Arshad R., 2015. Organisational Resources and Sustained competitive advantage of cooperative organisations in Malaysia. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 170: 120-127.

- Ozalp A., Yilmaz I., 2014. New Generation Cooperatives and Problems Analysis of Agricultural Cooperatives in Turkey. XI National Agricultural Economics Congress. 3-5 September Samsun.

- Ozdemir G., 2005. Cooperative-Shareholder Relations in Agricultural Cooperatives in Turkey. Journal of Asian Economics, 16: 315-325.

- Ozudogru H., 2004. Economic Analysis of Kirklareli Koy-Coop. Union and Examined of Influences to Cooperative Success of Managers. Journal of Turkish Cooperation Institution PhD Thesis, Ankara: Ankara University, 172 pp.

- Pashkova N., Niklis D., Alexakis D., Papandreou A., 2009. Food Marketing Cooperatives of Crete. A Financial Assessment within the EU Context. 113th EAAE Seminar. September 3-6 2009. Chania, Crete.

- Rehber E., 2011. Cooperatives. Ekin Publications.

- Serinikli N., Inan I.H., 2007. Economic analysis of Edirne Village Development Cooperatives Association, Tekirdag. Journal of Agricultural Faculty, 4(3): 237-248.

- Surmeli Y., 2006. Cooperative Management Analysis of Afyon Basmakci Number 2 Poultry Agricultural Cooperative. Msc Thesis, Ankara: Ankara University, 130 pp.

- Unal V., Yercan M., 2006. The importance of fisheries cooperatives in Turkey. Ege Univ. Journal of Water Products, 23(1-2): 221-227.

- Unal V., Guclusoy H., Franquesa R., 2009. A comparative study of success and failure of fishery cooperatives in the Aegean. Turkey. J. Appl. Ichthyol.: 1-7.

- Valentinov V., 2007. Why are cooperatives important in agriculture? An organizational economics perspective. Journal of Institutional Economics, 3(1): 55-69.

- XiangyuGuo M., 2010. Study on Functions of the Agriculture Cooperative in Food Safety. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia, 1: 477-482.

- Yener G.K., 2006. Financial Management. Productive Industrialist and Businessman Association. Istanbul.

- Yercan M., 1996. A survey on the use of resources in selected agricultural cooperatives in İzmir region and their effectiveness in cooperative enterprises. E.Ü. Institute of Natural and Applied Sciences Department of Agricultural Economics. Bornova İzmir: Doctorate Thesis.

- Yildirim I., Acar I., 1999. The Role of Agricultural Development Cooperatives in the Evaluation and Marketing of Milk and Its Products: An Example of Agricultural Development Cooperative in Van Dönerdere. International Convention on Animal Husbandry. September 21-24. İzmir: Ege University Faculty of Agriculture, 533-540.

- Yilmaz İ., Sayin, C., Mencet. M.N., 2008. Agricultural Cooperatives in Turkey: Current Status. Some Problems and Solutions VII. AIEA2 Congress. The Role of Cooperatives in the European Agri-food System. 28-30 May, Bologna.